My daughter loves to bake. More specifically, she loves eating the baking, so therefore she loves to bake. A couple of weeks ago, I arrived home from work to find her making banana muffins. She had finished preparing the batter and was about to start scooping it into the muffin tins. As I greeted her and took a peek in the bowl, I couldn’t help but notice that the batter was runny. Like, really runny.

I gently asked her if she’d finished putting all the ingredients in and she said she had, although she agreed it looked too liquidy. Just to be sure, I started naming off some of the dry ingredients. “You put the full 3 cups of flour in?”, I asked. “Yup”, she replied. “And you had enough baking soda?”, I probed. “Yes, I ran out of one box, but found the new box”, she said. Her demenour seemed confident enough and I didn’t want to take away any of the ownership of the baking from her, so I let it go. “Ah well, let’s see how they turn out – maybe they’ll be fine”, I said hopefully and we scooped (or more like poured) the messy, viscous batter into the tins. “Fingers crossed”, she added hopefully and we popped the trays in the warm oven.

After about ten minutes, we curiously examined the progress by peering through the lit oven window. Sure enough, the muffins were forming soft, high peaks. We both breathed a small sigh of relief. It appeared they were going to work out just fine after all! We let them finish baking and then carefully removed the trays from the oven and set them on the stove.

It wasn’t long before we noticed that the muffins weren’t sitting up quite as tall as they had been in the oven. The tops had gone from looking like majestic mountains to looking more like hills. After a couple more minutes, those hills were starting to ressemble flat grasslands. By the time the muffins had cooled, they were looking suspiciouly like banana-coloured hockey pucks. There was no doubt about it, they were utterly and hopelessly flat. Clearly, something wasn’t right.

To be fair, while not particularly puffy, the muffins didn’t taste terrible. We ate them all and they were relatively good. However, there was no question that there must have been an ingredient that was either missed entirely or one that was not represented in the right proportion. The muffins were okay, but they could have been so much better.

The Recipe of Our Equation

In the same way as baking, our unique equation acts much like a recipe. It is essentially our present-day recipe for fulfillment. By design, it tells us the full list of ingredients that we have identified as essential to bringing joy into our daily living. It also describes the amounts we desire of each ingredient. Just like a baking recipe, those amounts are not usually all represented in equal proportions. Too much of one thing can take away from another and throw things off. When something is missing entirely, it can really impact the result. And, like any good baker, there is often opportunity to improve upon the recipe through experience and experimentation.

Daily Analysis & Adjustment

So how do we ensure we’re living according to our designed equation and learning from it? On a daily basis, we can do this through our evening reflection. This involves identifying what clusters of activities you engaged in and in what quantities. In the example used in the article describing Evening Reflection and Gratitude, we had designed an equation for the day as follows: Purpose + Health + Kids. When we engaged in the end-of-day reflection, we noted that we had spent time in Purpose and double-time in Kids. At that point, we may use the Flexing Your Week strategies to work our missing Health component into an opportunity later in the week.

The daily analysis and adjustment that happens with the Evening Reflection is like zooming in on a single data point (or in this case, a specific day of the week). The learning becomes even more powerful when we zoom out from a single data point and begin to look for trends. So, let’s lift out of a specific day and look across the whole week.

Examining Our Week

It is important when doing the end-of-week analysis that we employ the mindset of a scientist as described in the Putting the Equation Into Practice article. We must make sure to keep our interest focused on learning and evolving, as opposed to accomplishment and judgement.

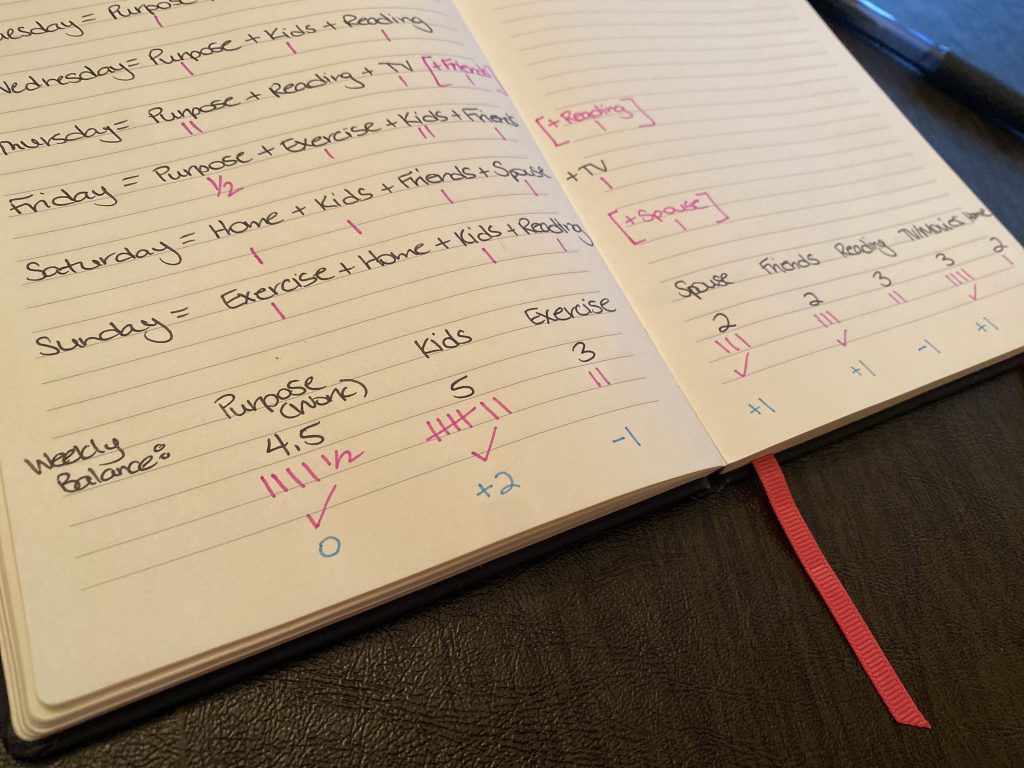

With that in mind, remember back to Building the Equation. Do you recall how we had the full equation for the week written at the bottom of our page before we broke the equation out by day? I call this the weekly balance line. When the week is over, take a moment to summarize all the tallies for the days under each corresponding cluster at the bottom of your page. For example, if you have a cluster called Exercise and you have one tally on each of Monday, Wednesday and Friday, then summarize this by putting three tallies under the label “Exercise” in your weekly balance section. Do this until all of the tallies across the seven days of the week are accounted for in your summary.

Looking Across All Clusters

What can we learn from looking back on our week? For starters, we can see how closely our reality aligned with our intentions. Begin by looking across all of the clusters. Do the number of tallies (representing time blocks spent on things throughout the week) add up to the number of blocks you had designed in your week?

It’s not uncommon for this to be wildly off the first time you use your equation. When I flip back in my notebook to the very first week I tracked my equation, I can see that I had 7.5 fewer tallies across all of my clusters than I had designed into my equation. There are really two reasons this might happen. Firstly, this can be helpful insight into whether your expectations are realistic in terms of the time you have for the things you want to do. I reviewed my equation again and decided that I’d been too ambitious in designing my equation to have 5.5 blocks for the cluster I called “Interests”. I made the decision to lower it to 4 instead and adjusted how this flowed into my daily equations accordingly. The second reason this might happen is that I may not be making the best use of my time. I set an intention to be more observant the following week about what exactly I was doing if it wasn’t spending time in my desired clusters. By the end of week 2, I was only 2.5 tallies shy of what I had designed. Much better!

Looking Within The Clusters

So we have the right ingredients, but how did we do on the proportions? Now examine how the summarized tallies in each cluster relate to your intended number of blocks spent in each cluster. Which clusters had more tallies than intended? Which had less? What does this say about the trade-offs you may be making with your time?

When I examined the summary after my very first week of using my equation, I could see that I had slightly more tallies for “Kids” and “Spouse” than I’d designed and much fewer tallies for “Interests” and “Exercise”. This was insightful for me because I could clearly see that my desire to say yes to everything my kids and spouse wanted to do was directly impacting my ability to do the things I had wanted to do for myself. I would either need to learn to say no to my family once in a while in order to protect the time I needed to invest in my own health and wellness, or alternatively make a conscious decision to adjust my equation (and therefore my expectations) of the time I was going to spend by myself knowing that the time with my family is precious. Either way, it now became my choice. This is key because without the observations and ability to choose, I knew that the result in the absence of my equation would be resentfulness toward my family and that is definitely something I would not want to happen. In my case, I decided to keep my equation the same and look for opportunities to practice protecting my time in the following week.

Blending Analysis With Intuition

Now that we’ve been looking at our week using our heads, let’s check in on our hearts. How do you feel? Our equations are fluid and can evolve as we learn more about ourselves. What did your experience of daily moments of joy tell you about where you most love spending your time? This is where we can adjust our recipe just as a good chef would do upon tasting their creation.

Perhaps you notice that many of your joy moments were related to reading and you want to adjust your equation to spend more time reading and less time watching TV. Or perhaps you notice that spending time in one cluster worked better on a particular day of the week than another and you want to officially swap those pieces of your equation between the two days. Go ahead and make the tweaks you’d like before writing out your equation for the next week.

Examining Across Many Weeks

We’ve zoomed out our reflection from a point in time (a day) to a broader period of time (a week). What happens when we zoom out even further? Stepping back and looking across a multitude of weeks can really help to highlight some insightful trends.

The approach to analysis is the same: first look across all clusters and then look within the clusters. After the first three months of my equation practice, I looked back at the weekly summaries to see if I could spot some trends.

The first thing I noticed was that most of the weeks had fewer tallies accounted for than what I had designed in my equation. After weeks of intention-setting and practice, I was still struggling to make the weekly balance. This was a good clue that, despite my initial small adjustment to the “Interests” cluster, I was probably still being too ambitious about the amount of time I had in a week. I decided to shave a few blocks off of the equation in a way that still felt balanced to me.

The second thing I observed was that there were certain clusters that were consistently low (meaning, less time actually spent than I’d planned in my equation): Interests, Self-Growth and Home Tasks. There were also certain clusters that were consistently high (meaning, more time spent than I’d planned in my equation): Kids, Friends and Spouse.

Seeing this on paper was really powerful. It allowed me to ask myself important questions, such as: Am I spending extra time with family and friends because it’s a great source of joy or am I spending extra time in those areas because they tend to be more externally-motivated (driven by others) rather than internally-motivated (driven by myself)? Also, if I’m not doing the home tasks because I’m not finding joy in them, is there a way for me to get help with those things? The answers to these questions can also provide you with information on how you may want to tweak your equation or where you want to bring additional awareness when doing your daily intention setting.

The Levers of Expectation and Reality

Overall, the analysis and adjustment practice is an exercise in coming to a point of intersection between your expectations and reality. To get them aligned, you can adjust either lever or both. This means, you can choose to change your expectations or you can choose to change where you’re spending your time or some combination of the two.

Here’s another example that I’ve noticed in my own multi-week analysis. I have a cluster devoted to “Home Improvement” with an allocation of two blocks of time a week. I don’t particularly like doing the home improvement stuff, but there are some clean-up and small renovation projects that I want done at home, so I make time in my equation to work on these. Of course, I do find joy in the result once the work is complete.

When I look across multiple weeks, I notice that I’m spending less time in this cluster than I’d planned. Not really surprising, as I don’t find initial joy in it. Yet, I do spend a lot of time frustrated that these projects aren’t further along. Not just because I’d like to have them completed, but also because when they’re mid-flight it often means that there’s some degree of mess in the house. At the same time, looking across multiple weeks, I also notice that I’m often spending more time engaged in my cluster labelled “Friends” than planned.

So, with my levers of expectation and reality, I have choice. I can adjust my expectations: “This house project I’m working on is going to take longer than I thought and I’ll need to be patient with it because it’s more important to me to spend time with my friends”. Alternatively, I can adjust reality: “Maybe I don’t say yes to every opportunity with my friends because I am really looking forward to the result of this house project and want to get it done”. Or perhaps there’s something in between.

If you choose to adjust your expectations, you’ll want to adjust your fulfillment equation accordingly. In this case, I would change the two blocks of time that I had allocated for the week to one block of time and I would make a point to myself that I’m going to have to be patient with how long the home project is taking.

If you choose to adjust your reality, you can lean heavily on your daily practice of morning intention setting, finding flow throughout the day and evening reflection and gratitude to ensure you’re devoting the time you would like to see the project through to the finish.

Perfecting Your Recipe

Looking back at the week or at multiple weeks can be really insightful. It’s like comparing the taste and texture of your finished baking to the recipe you’d designed. It allows you to make tweaks to your equation or to recognize when you’ve left out an ingredient that you’d carefully crafted to go into your week. Remember that just as the recipe should yield the most fluffy and delicious muffins, your equation should always stay focused on providing you with the most fulfillment in daily living. This means keeping it light and joyous, and resisting the urge to drive your equation toward productivity. The best way to do this is by keeping a curious mind and an open heart.

Read Next Article: Step 6 – Making It A Habit